Housing the Estates: Parliamentary Locations and Buildings

Over the lengthy history of Scotland’s parliament, the three estates met in a variety of diverse, and sometimes unusual, locations, as can be seen from the sites plotted on the interactive map below. Exactly where an assembly convened was dictated by a number of circumstances, from the expected turnout, the availability of existing accommodation or external factors affecting the choice of setting, such as war or disease. In general, early medieval open-air assemblies were superseded by more formal meetings in abbeys and royal palaces, which, in turn, were supplanted by secular municipal venues, eventually culminating in a move towards purpose-built structures independent of the royal environment.

It is generally accepted that parliament developed from the king’s court, or curia regis, a gathering of major office-holders, courtiers and other members of the royal household who served as advisors to the king and also exercised some judicial and fiscal responsibilities. Certain business required wider consultation and on such instances this core group would be augmented by the most important lay and ecclesiastical figures of the realm. Arrangements for meetings of the curia regis were largely ad hoc, and indeed the informal nature of the body meant that its core could simply accompany the monarch as he travelled around the kingdom. Business was often conducted wherever the king happened to be, hence some of the more unlikely locations for early meetings of parliament, such as Auldearn, the site of a long-destroyed royal castle, and perhaps the Forest of Tor, an established royal hunting ground.

Some favoured locations, however, not only lacked any traditional royal associations but also any obvious buildings in which a meeting could have assembled. Birgham, a minor settlement on the River Tweed between Coldingham to the east and Kelso to the west, was one such site. It was here, in March and July 1290, that two large and significant parliaments were held to negotiate the treaty under which the marriage of the Maid of Norway to Edward, Prince of Wales was agreed. With neither castle, parish church nor any alternative structure such as a teind barn thought to be standing at this location, tradition holds that the assembly convened in the open air on a site known as the Treaty Field, today the location of the local park. Meetings out-of-doors were not historically uncommon. Indeed, open-air assemblies played a vital part in the ceremonial of early Scottish kingship, best seen in the investitures carried out at the traditional inauguration place of the Moot Hill at Scone. The holding of assemblies in the open also offered easy personal access to the king, regardless of rank, and again indicates the relative informality of methods of consultation between the medieval monarch and his subjects.

It can be assumed that when the estates met in royal castles, the great hall would have been used as the venue, with the king’s own chamber perhaps sufficing for discussions concerning subsidiary business or even for smaller councils. Great halls were multi-functional, serving as a place for ceremonial feasting and investitures as well as a chamber of state where the monarch would hold court, literally and figuratively. Most medieval parliaments were brief affairs, rarely lasting longer than a week, so great halls would have been fitted out with temporary furniture in the form of removable trestle tables and benches. Perhaps only the monarch and the nobility and clergy would have been provided with a seat, the rest either standing or sitting on the floor.

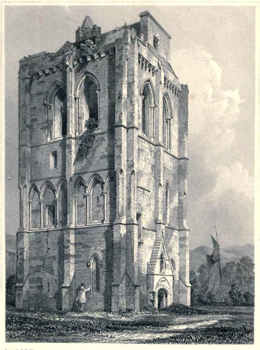

Cambuskenneth Abbey tower

Parish churches, convents and monasteries were also regularly chosen as the location for early parliaments, as the hall-like qualities of such buildings ideally suited the needs of assemblies larger than those that could comfortably be accommodated in a castle. The abbeys of Holyrood, Cambuskenneth, Dunfermline and Newbattle, for example, all played host to meetings of the estates at various times in parliament’s early history. As well as providing suitable living quarters for the king and other attendees in their adjoining domestic buildings, most monastic complexes also possessed a structure large enough for a substantial gathering, such as a refectory or the abbey church itself.

The national or patriotic associations of certain sites meant that some locations were favoured more than others. The Augustinian abbey at Scone emerged as a favoured meeting place of the early colloquia and councils in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, and it was here, in 1357, that David II (1329-71) summoned his first parliament after his release from 11 years of enforced exile. There is some evidence to suggest that ecclesiastical buildings, especially parish churches, had long been used for secular purposes, functioning as a venue for occasional sheriff courts, nascent local councils or important private meetings between men of influence. Thus, what came to be a regular use of such buildings for parliaments and councils was simply an evolutionary development on a larger scale.

Throughout the late fourteenth and early fifteenth centuries, Perth emerged as the preferred location for assemblies, partly due to it being at the heart of the power-base dominated by Robert, earl of Fife, later duke of Albany. After his release from captivity in England in 1424, James I also chose Perth as his main place of abode and continued the practice of holding major political meetings here. The convent-church of Blackfriars, a mendicant friary of the Dominican order, was already a popular venue for provincial ecclesiastical councils before it became the regular setting for parliaments in the 1420s and 1430s. Indeed, as the primary residence of the Scottish court, Perth almost came to be considered as Scotland’s first capital city. In 1437, however, James’ assassination in his private lodgings within Blackfriars brought any such plan to a violent and immediate end. His son’s coronation was held at Holyrood, not Scone, which was never again to accommodate a parliament nor even another investiture until 1651. The Scottish administration swiftly moved south of the River Forth to the sites of the principal Scottish fortresses. Edinburgh, the wealthiest and most populous burgh, already home to the treasury, archives and increasingly the exchequer, soon became the recognised seat of royal government.

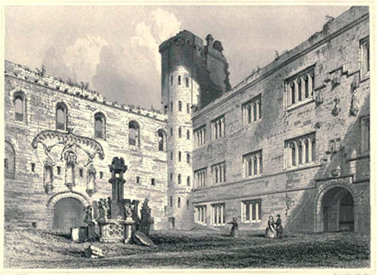

Linlithgow Palace courtyard

The reign of James II (1437-60) not only saw a rejection of Perth as the location for political assemblies but it also witnessed a break with the general tradition of holding parliaments within ecclesiastical buildings. It might have been expected that the royal residences would have been the natural settings for hosting the estates, and James I’s building works at Linlithgow Palace, for example, perhaps suggest that he had such a role in mind. However, it may have been the neutrality of municipal venues that immediately appealed during James II’s minority, which witnessed the usual factional struggles, specifically between the Livingstons and the Douglases. It is likely that the political community would have been reluctant to convene in buildings under the control of ambitious politicians, where they may have been liable to arrest or imprisonment.

After the parish church, the tolbooth was usually a town’s next largest building, typically containing a substantial hall above a vaulted prison, with an external forestair and steeple housing the burgh clock and bell. The tolbooth, or town-house, was the centre of local administration and justice in Scottish burghs, serving not only for the collection of tolls but as a meeting place for councils and courts and for imprisonment of criminals and debtors. Typically parliaments would have assembled in the room usually used as a council chamber, the most elaborately furnished and decorated within the building.

In November 1438, the estates gathered in the new setting of Edinburgh’s Old Tolbooth, situated on the High Street adjacent to the west front of St Giles’ Cathedral. Although this venue was to become a customary and regular location for subsequent meetings of the estates, it was clearly not yet viewed as the fixed seat of parliament. Where sessions were held still depended on the location of the king, and thus in March 1439 a council was held in Stirling and in June 1445 a parliament met in Perth. Significantly, however, the traditional venues of Stirling Castle and Blackfriars were forsaken in favour of tolbooths, suggesting that a conscious decision had been made since James I’s death to hold future assemblies in secular or civic buildings.

Apart from one session in Stirling, the parliaments of James III (1460-88) were all held in Edinburgh, which had indisputably become the centre of Scottish government and the country’s capital city. This was confirmed under James IV (1488-1513), whose parliaments all sat in Edinburgh’s Old Tolbooth. Indeed, it was mainly the threat of war or disease which forced parliament from its favoured Edinburgh base during the remainder of its existence. The exigencies of warfare had previously been the reason for the estates convening in some uncommon locations, such as Ayr, where two parliaments sat in St John’s Kirk in 1312 and 1315 as Robert I undertook military campaigns in the area, and Dairsie, where a session was held in 1335 whilst the Scottish leadership were besieging nearby Cupar. Hostilities with England in the sixteenth century saw the estates convening at locations such as Perth, Monktonhall and Haddington, while, later in the century, periodic outbreaks of bubonic plague in the capital saw the king’s household and parliament retreat to unaffected towns such as St Andrews and Linlithgow.

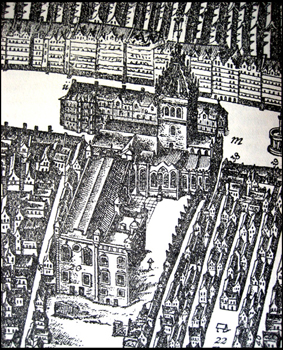

Detail from Rothiemay's map of 1647, showing

St Giles' Cathedral and Parliament House

From 1438 to 1560, the Old Tolbooth provided the estates with the most stable venue they had yet enjoyed. By the 1550s, however, it seems that the building was in need of structural repairs, and although these were carried out, they proved ineffectual. In February 1562, fearing the imminent collapse of the building, Queen Mary ordered the town to create new accommodation for the burgh council and courts that shared the tolbooth with parliament. Work started almost immediately. Two replacement tolbooths were built: the first was situated within St Giles’ Cathedral, where a wall was erected cutting off the western end, thereby providing a series of spaces to house the court of session, commissary, criminal and bailies’ court; the second, a new town-council house, was constructed outside the south-west corner of St Giles’ using the material salvaged from the partial demolition of the original structure.

There was no dedicated parliamentary chamber in either of the two new tolbooths, but, as the lesser courts were forbidden from sitting whilst parliament was in session, it was a relatively painless process to convert the court complex in St Giles’ into a parliament hall when the occasion required. Building work within the church was completed just in time for the parliamentary session held in June 1563. For this, and subsequent meetings, the estates assembled in the outer house of the court of session, situated in the central aisle of St Giles, whilst the adjacent inner house was commandeered for meetings of the lords of the articles. Some modifications to the space usually occupied by the session were necessary, such as the dismantling of wooden partitions, the construction of a dais on which to sit the throne and the provision of tables and seating for the use of the members. Once parliament had risen, the process was carried out in reverse and the layout of the courtrooms restored.

The new accommodation in St Giles’ played host to many subsequent meetings of the estates but Edinburgh was still some way off from being the fixed venue for all assemblies. Unlike parliaments, conventions of estates were much more likely to be held in royal palaces and were thus more peripatetic, probably because in many cases they were little more than an enlarged privy council, called at short notice to advise the king on a particular issue. In this respect conventions were more like the medieval curia regis, offering a relatively intimate and informal means for the monarch to seek opinions from the political community. Of the many conventions of estates held in James VI’s reign (1567-1625), for instance, locations included the royal residences at Falkland, Linlithgow, Dunfermline, Holyrood and Stirling. Such venues rarely, if ever, played host to a full and formal meeting of parliament. Although the earlier medieval practice of holding parliaments in royal castles and palaces was seriously impeded when hostilities with England became regular and prolonged and many of the traditional venues were garrisoned, captured or demolished, later attempts to hold parliaments in royal castles proved highly unpopular. In July 1578, a parliament was summoned at the fortified Stirling Castle, provoking a torrent of complaints concerning the lack of free access and requests for the meeting to move to the town’s tolbooth, the usual venue for parliaments held in the town. This was not granted but the protests did prompt a legislative response, the first act of this parliament being a declaration assuring ‘free access, liberty and freedom to resort and repair to the said castle … without stop, trouble or interruption’ [1578/7/1].

Apart from exceptional occasions caused by war or plague, for the remainder of James VI’s reign parliament convened at its usual Edinburgh home. The multi-functional space within St Giles’ Cathedral was adequate for the numbers attending in the late sixteenth century, which were typically less than 100. By the beginning of the seventeenth century, however, membership was on the rise and for grand ceremonies, such as the riding of parliament at the opening and closing of each session, it became evident that a large hall, with subsidiary chambers for the use of committees, would provide more suitable accommodation than that afforded by the current arrangement. There was already existing pressure on Edinburgh to provide improved lodgings for the privy council and the courts, in addition to a desire to reclaim the divided St Giles’ as a place of worship. Thus, in March 1632, the council set in motion a project to erect a purpose-built chamber, to be funded from a mixture of private subscription and local taxes.

19th-century view of interior of Parliament House

Parliament House, which was completed in time to hold the 1639 session of parliament, was situated close to the existing tolbooths, in the then-obsolete burial grounds of St Giles’. The structure was built on an L-plan, over partial under-building to compensate for the incline that sloped steeply away towards the Cowgate. The largest part of the building was a double-height main hall, to be used as shared accommodation for both parliaments and the court of session. Beneath the chamber was the Laigh Hall, the original use of which remains unclear, although it may have been called into use as a venue for subsidiary meetings outwith the main parliament or perhaps as a storage space. A smaller two-storey, two-chamber jamb, or wing, on the eastern wall of the main building contained an entrance lobby, with the inner house of the court of session occupying the rest of the ground floor and the court of exchequer situated above. During parliamentary sessions these rooms would have been utilised for accommodation by committees.

Although intended as parliament’s permanent home, within six years of the completion of Parliament House the estates were on the move once more. An outbreak of plague in the capital in 1645-6 saw parliament retreat first to Stirling, then Perth and finally to St Andrews in an effort to escape the spread of disease. In Stirling the castle was picked as the venue, though the circumstances were exceptional, with the fear of royalist risings perhaps influencing the choice of a defensive setting. The tolbooth in Perth was presumably the location for the meeting held there, whilst the public school and university library in St Andrews was used for accommodating the estates’ visit to the town. Parliament returned to Edinburgh for its session of November 1646, but was forced out of the capital once more by external forces only a few years later. The capture of Edinburgh after the Battle of Dunbar in 1650 led to Perth and Stirling hosting three additional sessions of parliament, before the Cromwellian occupation of the country saw Scotland, for the first time, ruled by a British Parliament in Westminster.

The modern Scottish Parliament Building in Edinburgh

With the Restoration of Charles II in 1660, parliament returned to its purpose-built residence in Edinburgh, where it sat for the remainder of its existence. Although still owned by the town council, after the Union with England in 1707 Parliament House was gradually taken over by the legal profession and, with subsequent nineteenth-century alterations and remodelling, became integrated into the national law complex, which houses the courts of session, criminal appeal, the Faculty of Advocates and the Advocates’ Library. The original seventeenth-century building has been significantly re-clad and enclosed by later architectural works, leaving it almost invisible from the outside, but the main hall in which the estates met is still largely intact and recognisable as a parliamentary chamber. Parliament House was to be the estates’ home for less than 70 years before historical events stripped it of its primary function. In 2004, however, with the advent of devolution, Scotland’s second purpose-built legislative chamber opened at the foot of the Royal Mile. Although radically different architecturally from its predecessor, its purpose is the same: to serve as a permanent home for Scotland’s parliament.

Further reading:

- The Architecture of Scottish Government: From Kingship to Parliamentary Democracy, Miles Glendinning, with contributions by Richard Oram and Aonghus MacKechnie, and an appendix by Athol Murray (Dundee, 2004).

- ‘Hosting the Estates’ in The Burghs and Parliament in Scotland c.1550-1651, Alan R. MacDonald (Aldershot, 2007), 131-156.

- ‘Housing Scotland’s Parliament, 1603-1707’ in Parliamentary History, 21:1 (2002), 99-130.

- Parliament House: A Short History and Guide, W. Douglas Cullen (Edinburgh, 1992).

- Tolbooths and Town-Houses: Civic Architecture in Scotland to 1833, the Royal Commission on the Ancient and Historical Monuments of Scotland (Edinburgh, 1997).